The Prison For Women in Kingston, Ontario, was built in 1933. Prior to its construction, women offenders served their time in the Kingston Penitentiary. Promiscuous women and those that fell under the wide umbrella of what we now call mental health issues were transferred to the nearby Rockwood Lunatic Asylum. At the Kingston Penitentiary, women were segregated from male inmates, they occupied various locations including basement cells and the prison hospital until 1913, when a separate building was constructed within the walls of KP, using prison gang labour. Known as the Northwest Cell Block, it housed exclusively female inmates. The conditions for women were not dissimilar to that of men: their cells were cold, dark, and damp, and they suffered the same corporal punishments including flogging, meals of bread and water, confinement to dark cells, and “the box”. However, unlike the men who were forced to engage in physical labour, the women participated in traditionally female activities, such as sewing and needlework. During the war, they produced thousands of pillowslips.

Twenty years after the opening of the Northwest Cell Block, the female population again outgrew its quarters, reaching a total of 40 women, some of whom were sleeping in corridors. It was decided that a separate institution would be constructed just outside the walls of KP, behind the Warden's residence. Again prison work gangs were conscripted to construct another limestone monolith: the Prison For Women, later nicknamed P4W. It was completed in 1933 for a total cost of $374,000. Strangely, due to overcrowding and a riot at KP, it's first inhabitants were men. In 1934, all 40 women were transferred from the Northwest Cell Block in KP, to the new Prison For Women across the road, under the care of Ms. Edith A. Robinson, Supervising Matron.

For 66 years, P4W would serve as the only federal women's prison in Canada, housing all women serving two years to life from all across the country.

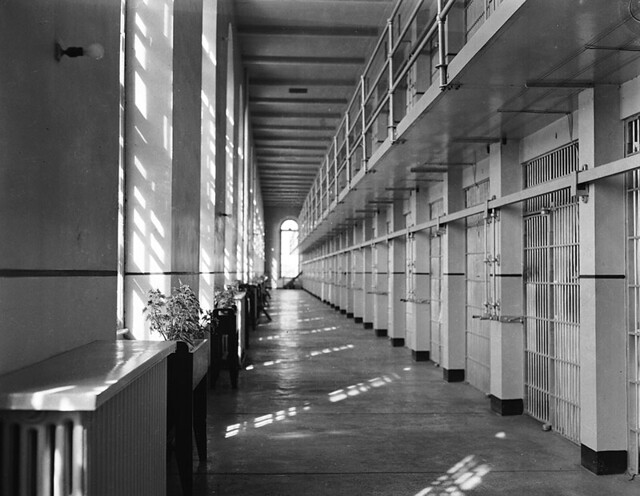

Unlike today's cluster model, which utilizes units or pods as opposed to linear cell blocks, and encourages interaction between inmates to help prepare them for life on the outside, KP and P4W operated on the Auburn approach, in which strict separation of inmates was thought to prevent undue influence on one another. KP and P4W shared similar architectural features influenced by the Auburn system: the cell walls separating inmates were extraordinarily thick, the ranges were long and narrow, and a towering perimeter wall surrounded the building and yard.

A 1936 royal commission found P4W had higher levels of security than was warranted given the crimes for which the women were serving time.

During the 1940s, the Elizabeth Fry Society became involved in rehabilitation activities and started many popular recreation and educational programs. The women began playing tennis, baseball, and volleyball, and taking classes in folk dancing and stenography. In the 1950s the library was expanded, and a beauty parlour was completed. Garden plots within the walled yard were offered to inmates and an ice rink was built in the winters. Improvements continued into the 1960s as more programming was instituted and skilled staff were hired, such as social workers and psychiatrists. A pre-release program was created in which women were driven around and escorted to parks and into stores. Additions to P4W were constructed as needed and in the 1970s the inmate count reached it's all time high of 210.

P4W Prison Glee Club circa 1955. (Photo found online)

Statistically, women at P4W were typically white and single, between the ages of 20-34. The percentage of Aboriginal women was disproportionate to the general population, and 18% of women were serving time for murder.

In the 1980s, after decades of controversy, it was finally recognized that P4W was not serving women's unique needs and treatment was unequal to that of men's. At this time, some women were transferred back to KP, to a special wing known as the Regional Treatment Centre. Women specific programming was created covering topics such as trauma and abuse. The need to decentralize the population of the federal female inmates was widely recognized, in part because many women never had a single visitor during their incarceration, due to the vast distances between P4W and their respective families spread across Canada's massive landscape.

Not unlike most prisons, controversy existed within the walls of P4W. At one point, women were the subject of unethical experiments with LSD. Suicides, hunger strikes, and self mutilations were reported. Over time, many studies concluded that the Prison For Women was inefficient and several recommendations were made that it be closed.

It is rumoured that a racist slur from a guard to a Native inmate led to the riot in 1994, when violent confrontations took place between guards and inmates. One guard was taken hostage and another was stabbed with a syringe. Fires were set and clubs were made from parts of bed frames. An all male emergency response team was eventually sent in to break up the riot and perform cell extractions. Women were strip searched and in some cases chained up naked for hours. Footage from the events later aired on television and the viewing public was outraged. Critics had been calling for it's closure for decades. Now citing clear research that the institution had become outdated given changes in correctional practices, they were starting to be heard. This riotous controversy would be the nail in the coffin for the historic Prison For Women. In 1996, it began transferring women to segregated units in male prisons, until they could be transferred to one of five new women's facilities that were under construction across Canada.

Joey Twins, serving life for murder (left) and Ellen Young (right) were two of the prisoners involved in the violent altercation with guards on April 22nd, 1994 (courtesy Maclean's)

P4W's most notorious inmate, Karla Homolka, called the Segregation Unit home until her transfer to a Quebec facility in 1997.

On May 8th, 2000, the last woman was transferred out and the Prison For Women began serving dead time.

In 2008, Queens University purchased the decommissioned prison, which had been assigned heritage status. Upon taking ownership, Queens immediately demolished almost all of the perimeter wall, leaving only a small section along the west side of the property, at the request of the adjacent neighbours. Queens planned to convert the former prison into an archival storage and office building, but those renovation plans were thwarted, as a majority of the building is protected by it's heritage status, and must be preserved.

The Prison For Women has sat vacant for over 13 years, holding it's

secrets within it's cold grey limestone walls. With their conversion

plan quelled, Queens turned off the heat, which of course triggered the

process of decay in the form of peeling paint chips and spreading

black mould.Let's go inside, shall we?

At the very moment night turns to day, darkness fades and the sun rises over the east side of Kingston, illuminating the long narrow southern A block. Even as the light creeps in, the darkness is still present. The silence is deafening only until an ambulance screams it's siren song at us as it whizzes by in a city that's still sleeping. We linger, sauntering in and out of cells at our own leisure with a freedom that can only be described as ironic. We sporadically stop and talk on the range, but we isolate and revert back to silence and introspection when we go into the cells. Then we gather again on the range and bask in the light of this new sun, allowing time to pass before heading to the other cell block.

The women were housed in two double decker ranges running parallel, back to back on the third and fourth floors.

With the sun finally rising, we venture around the corner and into the northern cell block, which is significantly shorter than it's counterpart.

You can feel the energy on these long cell blocks. You try to picture what life was like. You stand in a cold pink cell and put yourself in the shoes of a mother in her mid-thirties, nine years deep into a life sentence. The monotony. The prison politics. The beef. The repetition. The pain. The loneliness. The regret. The repetition. The laughter. The camaraderie. The love. The repetition. The hatred. The anger. The violence. And of course, the repetition.

It sends shivers up your spine.

Both of these ranges housed general population inmates. The cells were separated by thick walls and painted bright cheery feminine colours. Now a rainbow of purple, pink, orange and blue hues of paint chips are peeling and falling to the floor behind the bars of each cell. They crackle beneath our feet. Loneliness lingers in the stale air and we breathe it in.

Very few personal items remain, but a single toothbrush and a bar of soap resting atop a sink within one of the cells, brings the human aspect of it all to the forefront of my mind, again. The day to day of it, again. Some of these women served decades here. I cringe at the thought.

If these walls could talk.

On the other side of a hallway, at the western end of that southern cell block, we find ourselves standing in the Segregation Unit. This unit housed the most infamous and dangerous female criminals in Canadian history, as well as women that couldn't hack it in gen pop.

Deductive reasoning and connecting random dots leads us to believe that Karla Homolka was most likely housed in one of these gated cells on the second tier of the Segregation Unit. She is Canada's most notorious female convict, and she is now a free woman.

As we exit the Segregation Unit, we hear a sound. We pause in silence and listen to the glorious sound of nothing happening for somewhere between a few seconds and a lifetime. That look on your face is priceless.

Now we are venturing into the common area, where prisoners would engage in recreational activities, take classes, and participate in women centred programming, 12 step meetings and such.

We continue into the visitation area.

And then the prison infirmary.

Down in the dark and dingy basement, black mould is the only living inhabitant in the cold dark cells of the Administrative Segregation Unit. This unit housed inmates for specific durations of time for infractions committed within the prison, which could range from displaying negative behaviour toward guards, to possession of contraband or violent assaults. While serving time in Ad-Seg, prisoners would spend the majority of each day within their cell, only allowed out to shower and spend time on the yard a few times per week, or day, depending on the time period.

These two contrasting messages written upon the walls of adjacent Ad-Seg cells give a fragmented glimpse into the minds of the women that stood here before me.

Deeper into the basement we go. Turn on your flashlight.

We continue to wander and soak it all in, doing laps and getting acquainted with every square inch of the prison. We try to feel it as much as we absorb and experience it with our other senses.

The wheels located outside of each range control the simultaneous opening and closing of all cell doors. Manually turning the wheel raises the long black metal bar crossing atop the entire row of cells, which in turn raises the door latches. A handle on each cell also allows for individual cells to be opened.

After a glorious morning of exploring the Prison For Women, we are almost ready for our pending release. But first we return to the southern cell block, A block, where hours ago we watched the sun rise. We walk it one last time, and capture the late morning sun blasting in through the tall arched barred windows and illuminating the emptiness within.

This image depicting the Prison for Women A-Block circa August 1958 was found online.

And here we stand, over 55 years later.

And once again, we are set free.

Here's an interesting report on the riot from thecanadianencyclopedia

Co-written by Jerm & Ninja IX.

click here to check out all of jerm & ninja IX's ABANDONMENT ISSUES